The Great Vurm stomped through Shervage Wood, its body as thick as three oak trees with scale upon scale that were hardened by the years. Its stomach rumbled; rabbits and the occasional hare were slim fodder. The rich pickings of sheep and cattle had gone as the farmers of Crowcombe had moved to the Vale of Taunton, or other parts of the Quantocks, where dragons didn't roam. Even the ponies were sparse, cantering towards the sea and over to Exmoor.

Hunger used to make the Great Vurm angry but now it made him weary. Too old to venture far, he lay down in a sunny glade and stretched out on the dandelions and nettles. He rested his jaw on his foreclaws. The sun felt good on his ancient bones.

He remembered this glade; he had brought his daughter here when she was a young dragon. Her scales were translucent and she was unable to make a flame: just a few sparks and a puff of pale smoke. The Great Vurm had carried her on his back and they ate charred mutton for their lunch. His daughter liked the marrow, crunching her teeth on the mutton shanks and spitting out the wool.

The Great Vurm's golden eyes blinked and closed. His mouth turned up at its ends. His daughter had been so pretty, her red scales hardening into a fine-looking dragon. She was young and agile and could chase deer better than he could.

He had shown her where the farmers lived and how she could kill the men who were a danger to the dragons but she didn't want to kill humans.

'I like it when they sing and laugh,' she said.

The Great Vurm blew a stream of flame at a squirrel that had lingered on a branch. The blackened carcass fell to the foliage and was snaffled up.

'Father, where are the other dragons? I want to play with them and have fun as the humans do.'

‘You are a dragon, daughter, we don’t play.’

His daughter used to look in the pond at the bottom of the wood, coming back one day and saying, ‘My nose is enormous and my teeth are too big.’

‘What are you talking about?’ The Great Vurm said, ‘Your nose is for smelling and is long to help the flame spurt further. Your teeth are perfect for crunching and tearing.’ His shoulders shook, ‘Where do you get these silly ideas?’

'Don't mock me, Father. I want to talk to other dragons my age,' his daughter tried to fold her wings across her chest but they didn't go that way.

'There aren't any, daughter.' He sighed. 'You could be the last one. You have to get used to it. The humans are our enemy.'

She raised up on her haunches and flapped her growing wings, 'I'm not listening to you any more.' She launched into the sky, looped around the glade once, and flew south.

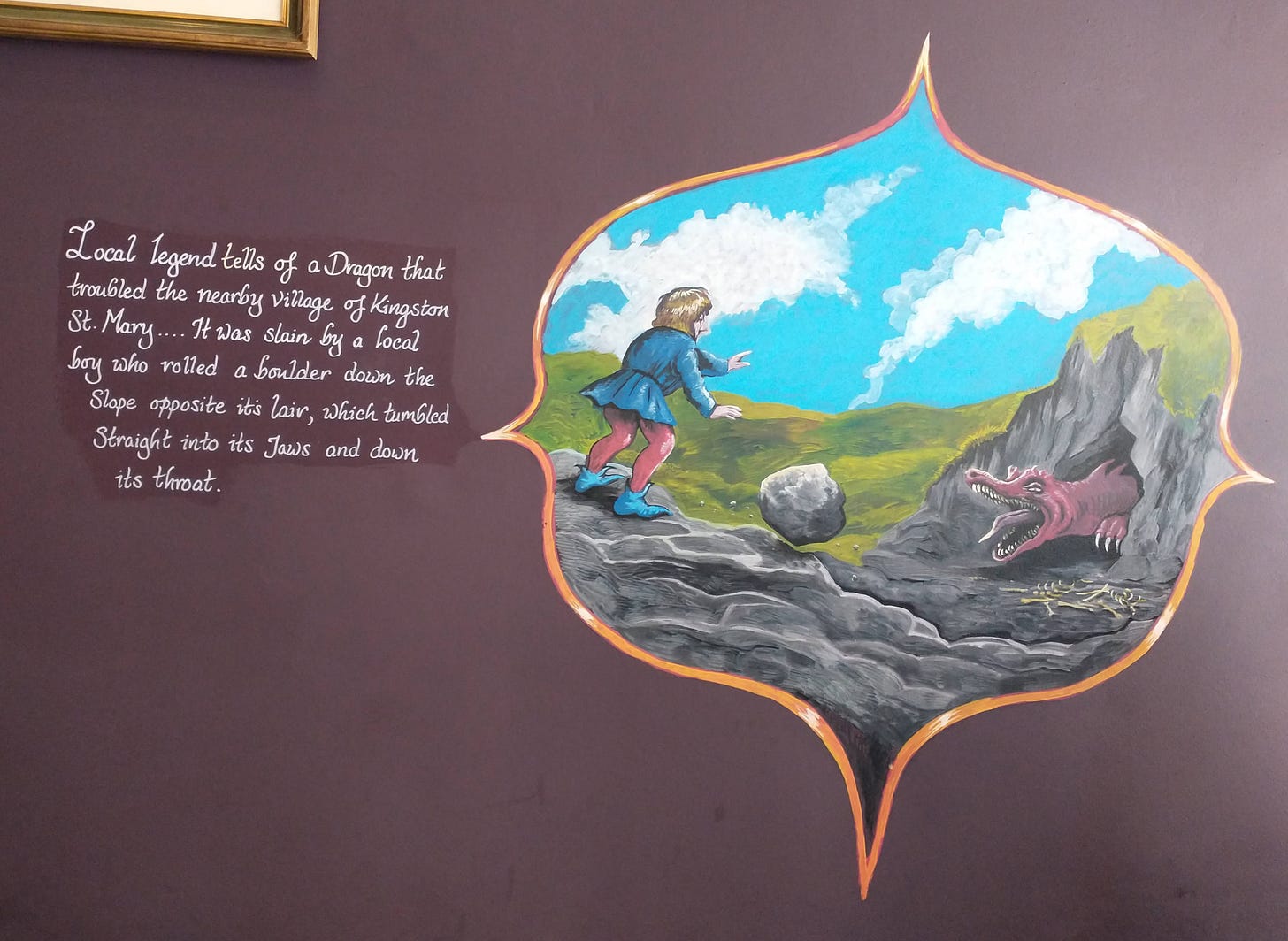

The Great Vurm had not seen her since. He had heard tale of a dragon at Kingston St Mary but that was a while ago. Passers-by were rare now. His golden eyes whirred and closed.

The villagers of Kingston St Mary shuddered. The stones in the church porch roof groaned, flames burst across the entrance and blood dripped from the gutter onto the grey slate paving. Two girls screamed, tightening their grip on their mother’s skirts.

The dragon was perched next to the square hamstone church tower having made its weekly kill of two sheep. The dragon launched into the sky and flew high up onto the Quantock hills. The slow, “whoomp, whoomp”, of leathery wings could be heard by the villagers and they coughed when golden dust fell from the porch roof.

The villagers emerged from the porch muttering and shaking their heads. The drizzle stopped. The tiled roof of the churchyard gate glistened as a beam of sunshine broke through the cloud. Thick smoke clung to the lower part of the village where the remains of a thatched roof smouldered. The rain had failed to extinguish the fire and the chain of pails passed from the pond to the cottage had done nothing but tire the arms of the frightened villagers.

‘Enough is enough,’ Trudy said, her coarsened hands on ample hips. ‘That roof is going to take months to fix.’

‘But it’s only a couple of sheep a week,’ Old Bob said, ‘Then it goes back to the hills and leaves us alone.’

‘It doesn’t though, does it?’ Trudy said. ‘It sits on the church tower like one of them hunky punks. It’s not even safe for the children to play outside.’

‘That’s right,’ another woman said, her face reddening as she spoke. ‘Bethany says it’s been watching her and the other girls do the washing by the stream.

‘Get on?’ Trudy said.

‘Yes, they ran back scared witless last Wednesday, leaving the wet clothes behind. My Rob had to wear his work shirt to church on Sunday.’

Old Bob coughed and hawked out a glob of phlegm that landed on a mossy stone in the churchyard. 'What do you suggest then? We're not fighters and the yeomanry won't come out of Taunton. They're too busy parading around and getting drunk.'

‘Well, something needs to be done,’ Trudy said.

Geoffrey the vicar raised his hands, 'We are all upset but none of us is hurt. We can afford to lose two sheep a week. Ours is only a small dragon. Those poor people in Cokethorpe are terrorised by the Great Vurm.'

'Aye,' Old Bob said, 'The Great Vurm has been there for years. He used to eat the livestock for miles around. We're lucky he's old and don't travel too far now.'

‘That’s alright for you to say, Vicar. Trudy jabbed a finger at him, ‘You ain’t a farmer and they ain’t your sheep. As for Cokethorpe, they’re strange in that village.’ She pointed to the west, ‘Too comfy with that monster, I heard.’

Children danced around the maypole, weaving in and out holding coloured ribbons, their tiny shadows flitting across the yellow grass of the village green. The closer they got to the maypole, the faster the children moved; the pipers and drummers struggled to keep up with the pace until the children had tied themselves into a knot and collapsed into a giggling heap.

John leant against the oak tree holding a mug of cider, watching the dance, tapping his foot. His red hair was tied back in a ponytail, his freckles cooling off in the shade.

‘You ready then, John?’ Old Bob joined him under the tree.

John took a swig of his cider and wiped his mouth with the back of his hairy forearm. ‘Aye. I reckon I am.’ He gave his tankard to Old Bob and strode towards the paddock.

Hay bales were scattered around the paddock behind the vicarage and villagers sat or stood upon them, chatting and drinking. Tables made from oak planks lying across cider barrels were covered with cloth and wooden plates stacked with pasties, flapjacks, pork pies, and apple cakes sat on top. Two tall cedar poles were dug into the ground, a crossbar was hoisted up with a rope and pulley held by a young boy with dark hair and a broken nose. Two hay bales lay on the grass in front of the obstacle, one smaller than the other.

The villagers gathered around the poles, nudging each other as the men limbered up with some deep knee bends and arm swings. Coins exchanged hands as the form was discussed. The older boys threw first, taking turns with their backs to the poles, holding the toggles attached to the twine around the smaller bale. One of them forgot to let go of the toggles and went tumbling backwards. The crowd laughed and the boy stomped off towards the vicarage, ears reddening. The men were next, every man in the village under the age of forty was lined up, even Geoffrey the vicar.

John, as defending champion, threw last. He strolled to the bale and looked around at the crowd. Three of the young women stood with mouths open. Abigail nudged Bethany who giggled and whispered to Mary.

‘It’s our time now, Old John,’ Egbert, a young man with curly hair who had cleared the bar easily, said and looked to his friend for acknowledgement.

John kept quiet and looked over his shoulder at the crossbar: a modest six feet. The crowd was hushed. John bent his legs and grasped the toggles. The beginners used their arms to lift and throw but John knew it was all in the legs and back. He used these early lifts to warm up and get his technique right. He breathed in, straightened his arms to get tension in the ropes and lifted his back and legs in one smooth motion before swinging the bale up and over his head, releasing his grip just past the apex. His feet came off the floor as he jumped backwards after the throw. The bale soared up and cleared the bar with four feet to spare.

The crowd clapped and cheered. John raised his big hand and swaggered over to Old Bob who sat on a stone bench. John plopped down and took a swig of cider. He rested his arms on his thighs, 'I'll let those young 'uns wear themselves out.'

The crossbar was raised three more times until at ten feet only John and Henry the blacksmith were left. Henry was shorter than John but had thighs that bulged through his beige breeches and forearms the size of lambs' shanks. Henry grunted as the bale scraped over the bar. It landed heavily and the crossbar wobbled before falling with a clatter.

John walked over, ‘You were standing too close to the bar, lad.’

Henry grunted, his black beard muffling the sound. His broken nose meant that he breathed through his mouth and rarely spoke. He kept his eyes on the ground, avoiding the gaze of his customers who filled the crowd.

John’s bale cleared the bar by a foot. The crowd clapped and cheered. The three girls jumped up and down. John raised his clasped hands above his head, smiling at the admiring onlookers. He winked at the girls.

Trudy shook her head, ‘Show off.’ Her husband loved the attention.

The crowd surged forward, patting John on his back and shaking his hand.

Mary put both her hands on John's biceps, 'Ooh, they're big!' She said and ran over to Bethany, whispering in her ear. They giggled.

The girls knelt by the stream scrubbing their families' weekly laundry in the cool water. Their skirts were tucked into their hems, their thighs and calves tinged red from the sun. They talked and laughed as they wrung out the sodden clothes, beat them on smooth rocks and hung them on low-hanging branches to dry. They waded into the stream and gripped the sandy bottom with their toes.

A shadow passed overhead. The girls looked up but the sun was beaming down with no clouds in sight. They laughed again, kicking water at each other.

A breath of wind rustled the leaves and another shadow passed. The dragon landed in the field above the stream. It folded its wings, waddled forward and rested its chin on the five-bar gate.

The girls stood, petrified.

‘What’s it doing?’ Mary said from the corner of her mouth.

‘I don’t know.’ Bethany said.

‘Shall we go?’ Abigail lifted a cold foot out of the stream.

‘The clothes ain’t dry yet,’ Bethany said. ‘My Ma will kill me if Father has to wear his work shirt to church again.’

‘My toes are wrinkly,’ Abigail inspected her other foot.

‘Why is it watching us?’ Mary tilted her head.

The dragon shuffled its paws and curled its tail around the side of its body. A robin hopped onto the dragon's scaly spine, breaking into song. The tip of the dragon's tail twitched, and its golden eyes, unblinking, peered at the girls beneath bony eyebrows.

‘Its eyes are beautiful,’ Mary said.

‘We should go before it gets angry.’ Abigail sloshed her way to the stream bank.

‘Do dragons even eat humans? It doesn’t seem angry.’ Bethany said. ‘Or hungry.’

‘I’m going to say, hello,’ Mary tiptoed along a series of smooth rocks. ‘Hello, Mister Dragon.’ She waved.

‘What are you doing?’ Bethany followed behind. ‘It might not speak English.’

Mary tilted her head and gazed into the dragon's eyes. The cold of the stream was forgotten, and her stomach felt warm and comfortable, 'It seems to know what we are thinking,'

‘We know what your thoughts are!’ Bethany nudged Mary.

The brown flecks in the dragon’s eyes spun faster.

Abigail sidled beside her friends and gripped Bethany’s elbow, ‘Let’s go.’

‘Ouch,’ Bethany pulled her arm away.

‘Look,’ Mary pointed.

The dragon sat up on its haunches and spread its scaly wings, the sun highlighting the red membrane as if the wings were on fire. The robin flew away.

The girls clutched each other.

The dragon tilted its massive head on either side and then sat back down, folding its foreclaws underneath, and resting its chin on the gate once more.

‘Ah, it was just stretching,’ Mary said.

‘Like a cat,’ Bethany released her grip. ‘Maybe it is friendly, after all.’

‘Do you think it will purr if I tickle its ear?’ Mary walked up the slope and the other girls followed, barefoot and breathless.

The villagers threshed and cut and baled the hay. They dug up, pickled and stored the vegetables. Mist hung low over the fields in the mornings, the crisp, cool air warming up as the sun rose.

Abigail, Mary and Bethany struggled to work in the field, their protruding stomachs made bending and carrying difficult. Abigail was sick three times one morning, and her mother questioned her.

‘Nothing’s wrong, Ma.’ Abigail swallowed some bile.

‘I’m calling in Arden Goodwife,’ Ma strode out of their cottage.

The Goodwife confirmed Ma’s suspicion. ‘She’s not the only one, Mary and Bethany are showing signs too.’ Her morning had been spent pressing her ear to swollen stomachs.

‘I knew it,’ Ma’s face reddened. ‘You’re always showing your ankles to them that wants to see them. Who did this to you?’

Abigail looked at the earth floor, wishing she had not listened to the other girls.

Geoffrey the vicar raised his hands, 'Ladies, ladies, please be quiet.' The myriad of conversations subsided, and the three girls huddled together. The beleaguered vicar took a breath to ask a question.

‘They’ve got to get married,’ Bethany’s mother said. ‘All of them.’

‘But they won’t tell us which men did it,’ Mary’s mother said.

Geoffrey let out his breath and took another, unused to having six women in his house at once. He preferred discussions about weddings and christenings, preferably in that order, with two people at a time.

‘It weren’t no man,’ Mary said.

‘No man? A boy then?’ Her mother grabbed Mary’s arm. ‘I saw you making eyes at Egbert.’

‘No, Ma, it weren’t Egbert.’

‘Who was it then?’

The girls looked at each other. Mary nudged Bethany who looked at the floor and mumbled, ‘It were the dragon.’

‘Lord save us,’ Mary’s mother said.

Geoffrey made the sign of the cross, ‘Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field.’ If in doubt, quote scripture, was his creed.

‘You poor loves,’ Bethany’s mother cuddled her daughter.

Voices murmured inside the church hall, and snippets of conversations rose to the oak rafters when lulls appeared.

‘This is the Devil’s work.’

‘How is this possible?’

‘The poor innocent girls have been led astray by the evil serpent.’

‘What shall we do?’

Arden Goodwife was backed against a trestle table, a press of villagers barracking her with questions.

‘They are too far gone for my herbs to work,’ she said for the fourteenth time that evening. ‘And I don’t know if they are going to have a baby or lay an egg.’

Bethany’s mother clasped her hands to her wrinkled cheeks, ‘An egg!’

Trudy was scratching her brow, ‘Are they giving birth to dragons or devils or humans?’

Arden Goodwife shrugged, ‘We will have to wait and see.’

Old Bob spoke from his bench, ‘I heard talk of a girl born in Kilve who had a fish’s tail.’ The villagers turned away from Arden who sidled away from the table.

‘They say she could swim like a fish and sing like an angel,’ Old Bob said.

The villagers crowded around Old Bob eager to hear more from the willing storyteller.

Over the next few days, the three girls stuck together. Excused working from the fields, they walked around the village with bowed heads and hands clasped over their bellies. Whispers and glances followed them like malignant shadows.

The church was full on Sunday when Geoffrey the vicar gripped the wooden pulpit and issued stark warnings about temptations and vices. ‘The serpent beguiled me, and I did eat,’ he quoted. ‘And he laid hold on the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil and Satan, and bound him a thousand years.’

The villagers shuffled their backsides on the cold hard pews. The girls had a pew to themselves below the pulpit where they bowed their heads even further.

Geoffrey raised his hands, 'But we must forgive these poor girls, they have been led astray by a wicked beast.' He smiled down at them. 'The infernal serpent, he it was whose guile, stirred up with envy and revenge, deceived the mother of mankind.'

After the service, Geoffrey stood inside the porch and wished his parishioners a safe journey and a restful Sunday. Fathers grabbed their daughters and took them straight home. Mothers tsked and tutted. The young children ran out to the pond and skimmed stones to see who could get one to land on the other side.

The dragon swooped low over the village. It flapped its wings twice and soared up to the field by the stream, it banked left and a wingtip brushed the tree tops. No girls were doing their washing today. It flapped again and glided across the lower fields where the villagers threw themselves behind the flammable hay stacks to remain hidden. The dragon extended its talons and grabbed a sheep in each foreclaw, its tail dragging in the grass for balance. The sheep squealed as they were carried back up towards the Quantocks.

John stood up and brushed hay off his jerkin. His forearms were bleeding; he had dived hard onto the sharp stubble. He walked to the middle of the field to join the other harvesters.

Trudy spat out a piece of straw in the direction of the distant dragon, ‘We have to do something.’

Rob the farmer shook his head, ‘We can’t make the girls unpregnant.’

‘We can stop it from happening again,’ Trudy turned to Rob.

‘What can we do?’ Rob picked up his scythe.

Fulton, Rob’s son, ran across the stubble to the group of villagers. ‘Da, Da, I know where the dragon lives.’

'Don't be silly, son.' Rob rested his hand on Fulton's curly hair. 'This is grown-up talk.'

‘I do, I do.’ Fulton squirmed out of reach. ‘I followed it up to the source of the stream. There’s a cave at the bottom of the spinney. It lives in there.’

The villagers crowded around Rob and Fulton.

‘Is that true?’

‘If it has a home, maybe we can kill it there on the ground?’

‘But who can do that?’

John felt the eyes of the crowd upon him, ‘I ain’t no sword fighter.’

‘What’s the point of having all those muscles if you don’t use them?’ Trudy stabbed a finger into his chest.

John shifted his weight, sweat gleaming from his brow, 'I can't fight a dragon.'

Fulton raised his hand, ‘You don’t have to fight it. You can just trap it in its cave. There’s a big boulder in the spinney that you could roll down.’

‘Yes, that’s it.’

‘Good idea.’

‘Well done, lad.’

The villagers patted each other on their backs and nodded their heads, happy with making a decision that didn’t require them to do anything.

John looked around the villagers, his head and shoulders above them all. There was no hiding from this crowd.

‘That’s agreed then,’ Trudy said. ‘When are you going to do it?’

‘Why not now?’ Rob said.

‘Yes, now,’ the crowd agreed.

John pulled out his red kerchief and mopped his freckled brow, 'I'll go tonight when the dragon's asleep.'

The harvesters resumed their work, singing while they cut and tied the hay.

The golden moon rose above the village, fat and heavy looking as if struggling to reach the stars before deciding to give up. John could see his breath cloud sit in the crisp air as he puffed up the hill, Fulton's shadow skipping along the path in the moonlight ahead. How have I got myself into this mess?

‘There, there,’ Fulton jumped up and down as he pointed. ‘The cave is there.’

John looked. Blackness in the side of the rocks.

‘Here’s the boulder, right here,’ Fulton’s whisper disturbed the night silence.

John put his hands on the mossy boulder. Cool and damp. That has not moved for a while, if ever. But it must have got there somehow. He bent down and shut his left eye, holding his right thumb up and squinting at the cave, ‘Are you sure the dragon is in there?’

‘It goes there at night.’ Fulton nodded.

‘You had best go, in case it comes out,’ John picked up a hefty branch. ‘This’ll do.’ He stuck one end into the soft earth behind the boulder. ‘Off you go, lad.’ He grunted as he pushed the branch as far under the boulder as he could.

Fulton skipped off to the copse and scampered up the low-hanging branches of an oak tree. He sat with his legs on either side of a branch and his back against the trunk.

John tripped over a root in the boulder’s shadow and fell onto the ground. ‘Ow,’ he shouted as his shoulder hit a sharp stone. He rolled to his knees and dusted off his jerkin for the second time that day. He circled his shoulder forwards and then backwards. It moved fine.

He froze.

There was an orange light in the cave. It moved. A jet of flame issued out of the cave and sparks flew up into the sky.

'Bugger,' John scrambled behind the boulder. He put all his weight onto the branch end, his feet dangling in the air. The boulder shifted forward. John shoved the branch further under the boulder and jumped on the free end again. The boulder shifted out of its divot. John jumped into the hollow, squatted down and heaved. His calves strained as he dug into the dirt, tiny steps at first as he pushed, then longer steps as the boulder tipped down the slope, and gathered momentum. The flame passed either side of the boulder, the heat singeing John's fine hair, he pushed and slipped forward. The boulder moved faster, engulfed by flame, and then a crunching sound and blackness.

‘You did it, you did it.’ Fulton scrambled down the tree and ran over to the dragon.

Its mighty jaws were clamped onto the boulder and smoke rose from its nostrils into the night. The golden light in its eyes faded before extinguishing into blackness.

Richard the woodcutter toiled up the slope carrying his parcel of cheese, bread and cider in one hand and his great axe in the other. His lunch was given to him by the nice lady in Crowcombe who had seen the axe and listened as Richard told her that he looking for a flat site, close to water, where he could build a cabin or house.

She told him that no one owned this land and there was plenty of wood to use or even the stone from Triscombe quarry. She was ever so helpful in giving directions to the stranger trying to find a place to live.

The slope eased and Richard's tired thighs welcomed the relief. The thought of the cool cider was on his mind, acorns crunched underfoot, and he thought about keeping a few pigs up here too. The noon sun beamed through a gap in the forest and Richard decided to have his lunch when he saw a large fallen tree trunk in the middle of the glade that would make the perfect seat. Richard jumped up and unfolded his linen parcel, he uncorked the cider jug and took three deep swallows.

The tree trunk moved.

'Get off me,' the head of the Great Vurm turned, his golden eyes glaring at the audacious human.

Richard jumped back, cider spilling down his jerkin. He grabbed his mighty axe in both hands and swung it up and then down without thinking.

The Great Vurm was cut in half. 'Aagh,’ he cried. His head, torso and foreclaws, trampled across the flowers. The wings, tail and haunches leapt into the sky and flapped unsteadily above the trees. Instinct took it north, towards Kilve and the sea, where all dragons go to die.

Richard raised his axe again.

The once Great Vurm howled in anguish, his golden eyes were traced with red. ‘I am doomed,’ he said, his head swaying from side to side.

Richard lowered his axe and watched the pitiful beast thrash around.

‘Daughter. Daughter, where are you?’ The Great Vurm stretched his neck up to the sky before dragging his torso through the undergrowth towards the noon sun, due south.

A trail of broken ferns and bushes lay in the trail of the once Great Vurm. His foreclaws ached from the unusual effort. Two talons had fallen out and blood oozed from cracks between its scales. ‘Daughter,’ he cried out. ‘Where are you?’ He gripped the earth and dragged himself forward some more. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said.

He dragged himself up over the brow of a small mound of leaves, rustling his way through. The Hamstone tower of Kingston church was golden in the setting sun, and the sound of humans laughing reached him from nearby. He followed the stream downhill, one aching drag at a time until he could see the small pond. Three children were skimming stones across the water, their ginger hair highlighted in the sun as if it were on fire. Three women sat on a flat boulder, laughing and smiling. A man in a black coat stood beside them, a silver cross hung around his neck.

Laughter. That is what his daughter had wanted. She loved listening to it. Where was she? His breath rattled in his mighty chest. His strength, once immense, was ebbing away. His eyes were more red than gold now.

The man with the cross left the laughing group of humans and strolled up the path. The Vurm tried to hide in the leaves; it was too tired to kill now. The man stopped when he thought he saw a tree trunk move.

‘Oh,’ Geoffrey the vicar said.

‘Human,’ the Vurm gave up trying to hide. ‘Where is my daughter?’

'Daughter?' Geoffrey said. His face screwed up in thought. 'The dragon that lived here? It’s dead.'

‘Dead, human?’ the Vurm’s breath wheezed. His weakened heart tightened in his scaly chest.

‘Yes.’ Geoffrey drew himself up to his full height to look down on the Vurm. ‘Killed a few years ago by Big John.

‘Why did he kill her?’ The Vurm dropped his jaw onto the soft ground. ‘She would never harm any humans.’ He stretched out his foreclaws and lay on his side. ‘She wanted to laugh and play.’ He coughed and a few sparks fizzled out on the moss.

Geoffrey looked at the Vurm and then back down to the pond where the children were throwing bigger stones over the pond. ‘She was a she?’ he said to himself.

The three women stood. Bethany, Mary and Abigail peered up at the vicar.

‘Daughter, I am sorry,’ the Vurm said. His weary eyelids closed.

One of the children skipped up the path on his chunky legs to stand beside Geoffrey. The child reached forward with a freckled hand and placed it on the Vurm’s nose. He stroked the scales and turned to Abigail.

‘Ma, he’s dead.’

The End

Merry Christmas to you all. Thank you for subscribing and reading.

Excellent! Happy Christmas.